Applications of Instrumental Variables (IV)

Summary

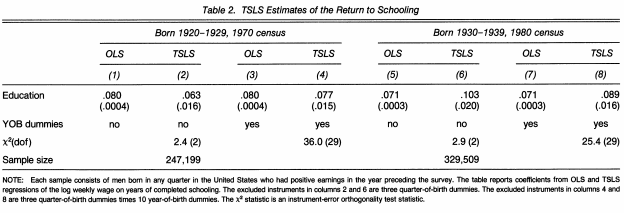

Estimating the Return to Education

Experiments

Q: How would you measure how much an additional schooling would impact one’s income?

This is difficult to answer as there exists an “ability bias” in estimates of the economic return to education that more able idividuals in the labor market get more schooling, perhaps because of better access to captical markets. Angrist et al. addressed the potential bias in “years of schooling” using “quarter of birth” as an intrumental variable for education and claimed that an additional year of schooling would bring around 8-9% increase in weekly earnings in their publication [1][2]. Individuals’ season of birth is related to their educational attainment because of the combined effects of school start age policy and compulsory school attendance laws. In most school districts, individuals born in the beginning of the year start school at a slightly older age, and therefore are eligible to drop out of school after completing fewer years of schooling than individuals born near the end of the year.

Framework

\[Y = \gamma_{0} + \gamma_{1} X_{1} + \rho S + \epsilon\] \[S = \delta_{0} + \delta_{1} X_{1} + \delta_{2} X_{2} + \eta\]- \(Y\) : ln(Weekly Wage)

- \(S\) : Years of Schooling

- \(X1\) : Years of Birth Dummies

- \(X2\) : Quarter of Birth IV (with Compulsory School Attendance)

- \(\gamma, \delta, \rho\) : vectors of coefficients

Conclusion

- an additional year of schooling would bring around 8-9% increase in weekly earnings.

- 25 percent of potential dropouts remain in school because of compulsory schooling laws.

- a valid identification strategy because date of birth is unlikely to be correlated with omitted earnings determinants.

- return to education is close to the OLS estimate, suggesting that there is little ability bias in conventional estimates.

Note

Angrist et al. introduced the concept of Local Average Treatment Effect (LATE) for Instrumental Variables (IV) [2][3], where the treatment effect for the subset of the sample that takes the treatment if and only if they were assigned to the treatment. In an ideal experiment, all subjects assigned to treatment are treated, while those that are assigned to control will remain untreated. In reality, however, the compliance rate is often imperfect, which prevents researchers from identifying the ATE. In such cases, estimating the LATE becomes the more feasible option.

- Angrist, J. D., & Keueger, A. B. (1991). Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings?. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 979-1014.

- Angrist, J. D., & Imbens, G. W. (1995). Two-stage least squares estimation of average causal effects in models with variable treatment intensity. Journal of the American statistical Association, 90(430), 431-442.

- Angrist, J. D., & Imbens, G. W. (1995). Identification and estimation of local average treatment effects (No. t0118). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Treat vs. Intent-to-Treat in Online Experiments

Estimating Network Effects Using Naturally Occurring Peer Notification Queue Counterfactuals Two-Stage Least Squares For A/B Tests From Twitch